Welcome back.

In the previous post, I discussed the definitions of dissociative and associative mechanics. Today I want to cover a more complex application of those ideas.

Rather than discuss individual mechanics, today I discuss how dissociative and associative decision-making impacts the racial design of tieflings and gnomes, two iconic races in the tabletop roleplaying game, Dungeons & Dragons (D&D). In particular, I want to unveil as much of the methodology that went into their design as possible, and to present some do’s and don’ts for any reader who is adding races to their own world, whether it be from a game mastery (GM) standpoint or as an indie designer.

Before we dive into it, a preface: no race is fully dissociative or associative. At some point, a designer must create the race. This adds the dissociative aspect. At some point narratives will be generated about that race, in games or in other media. This adds the associative aspect.

I treat dissociative and associative as extent descriptors of things which exist along a spectrum, not as absolute categories in their own right.

Let’s begin.

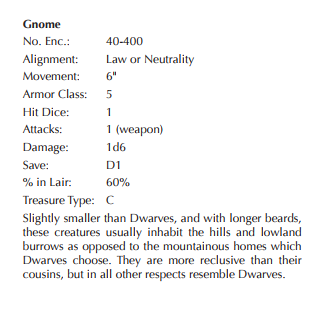

Gnomes first appear in the 1974 Dungeons & Dragons book. In their inception, gnomes were not a playable race, but rather an encounter option – a monster entry:

They are defined similarly to any other monster, even having a “lair” and a “treasure type” associated with them – sure signs which they were meant to be fought and killed. Their appearance is exactly that of dwarvenkind, except smaller, bearing longer beards, and having a more reclusive personality. From the outset, we can see that compared to the other monsters available in the same book, they aren’t particularly interesting…indeed, they strike me as the sort of monster that would be cut out in future editions of the game.

Instead of being cut, gnomes officially become the fifth playable race four years later, in Advanced Dungeons and Dragons, 1st Edition.

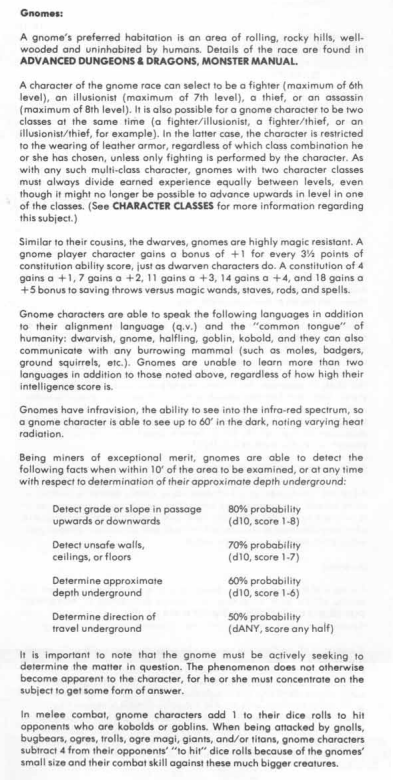

You can see other elements of the gnome entering into the equation – they gain a resistance to magic that they didn’t have before, and they also have classes which they are locked to – fighter, illusionist, thief, and assassin. They remain related to dwarves, and it’s notable that their magic resistance is actually derived from dwarven magic resilience. We see a more dwarven derivations in their infravision, their dungeon topography traits, plus this racially augmented ability to hit kobolds and goblins for no listed reason whatsoever – perhaps they share the dwarven hatred of goblinoids?

…if your gut reaction is that this race seems contrived – that is to say, largely dissociative – you’d be right . In a Q&A about Dungeons & Dragons, Gygax explains that gnomes were included because he just wanted another options.

“I added gnomes to D&D to broaden the choices for non-human PCs, as I did in AD&D. This was done because a number of players, myself included, were tired of having so many dwarves, elves, and halflings in the group of adventurers. In my campaign a party of 12 would have three front rank halflings, a second rank of dwarves, elves in the third rank, and the fourth rank the humans…”

(Gygax 2002 178)

He goes on to say that he built gnomes out of what he remembered of the four elementals of Paracelsus, of folk tales and folklore about mine spirits. These disparate sources further exacerbate their identity crisis. After all, neither the four elementals nor mine spirits are related, in their original form, to dwarves in any way.

The attempt to ground gnomes in players’ minds was advanced further through the Dragonlance novels. This establishes a narrative and justifies design decisions from an associative standpoint rather than a dissociative one, but the implementation was messy. The Dragonlance tinker gnomes lack any connective tissue to the original conception of the gnome, but have endured nonetheless throughout the editions. World of Warcraft firmly cemented technologist gnomes into our cultural consciousness, despite still not having consistent lore with the original Dragonlance tinkers. Mike Mearls, one of the lead developers for 5th edition, cited his own love of these tinker gnomes:

The entire progression of the gnome follows this meandering path, mostly driven by dissociative necessity rather than adherence to their associative roles in fantasy worlds. In the interest of not overly exasperating the reader, I shall rush through the rest of my observations:

If you look at rock gnomes, they used to be explicitly different from tinker gnomes, until suddenly the two are just fused together as just a generic “gnome” in 3rd Edition for convenience’s sake – a dissociative decision for ease-of-reading (Cook 2003). 3rd Edition also gives gnomes the favored bard class, something which had never been part of their lore before because no other race had taken up the bard class. Elves had taken wizard, which was the gnomes’ old go-to class due to their unique affinity with illusions – so they were largely pushed to become bards in the interest of filling up that space – another dissociative decision. In 4th Edition gnomes gained an abundance of fey flavor as a way of fleshing out the feywild (associative) and then in 5th Edition, both fey and tinker gnomes became available, but under the monikers of “forest gnome” and “rock gnome”.

The common thread to many these changes is that they were reactive to alterations in the game, rather than due to any care paid to who gnomes were in the fantasy milieus that D&D emulates. The times when they were altered to associatively reflect the world they lived in, once with the Dragonlance novels and once with 4th Edition, provide what actually grounds them in the fiction.

Let us now contrast them with tieflings.

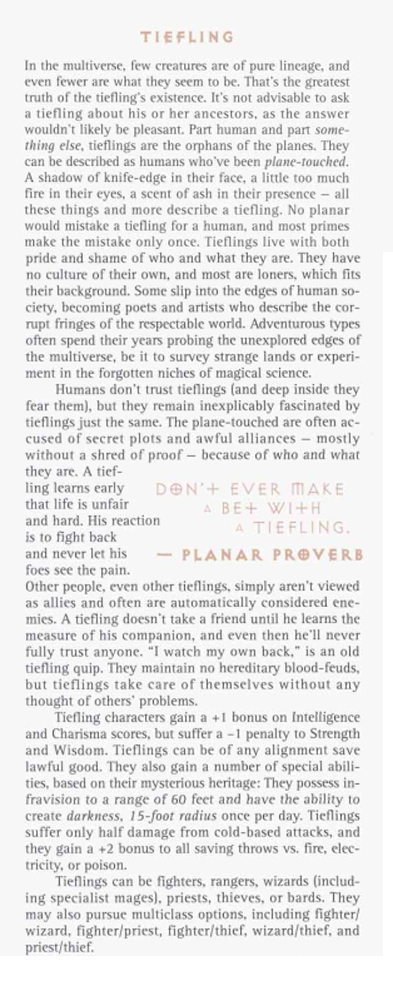

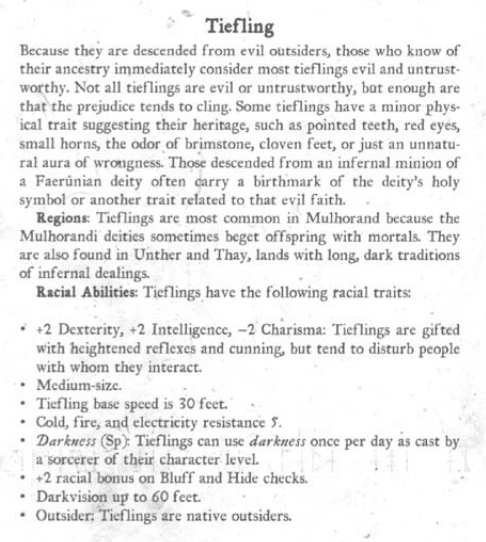

Tieflings do not start as a random encounter. They were not introduced at all until the Planescape Campaign Setting was released for Advanced Dungeons & Dragons, 2nd Edition (1989). Their debut…well, I’ll just show you:

It’s a refreshing read, isn’t it? They’re offer both a new in-world space for players to explore with their lore, and also have a new racial mechanic: they’re the very first playable race with elemental resistances. Without developer comments, it’s hard to know if this was more of an associative or dissociative decision, so it’s a toss-up.

Certainly, Planescape is propped up as the campaign setting with the most evocative writing. Certainly, it is valid to suggest that as such, my comparison isn’t utterly fair.

But let me rehash the goal here: I talk about tabletop RPG design, harvesting what I can from existing tabletop RPGs to inform my (and your) design principles. Leave your personal preferences for tieflings and gnomes at the door for a moment.

You can immediately see that tieflings are crafted with a strong dose of intentionality behind them – they aren’t just here to be “yet another player option,” they lend life and depth to the Planescape cosmology. As “orphans of the planes”, their identity carves a niche far beyond the existing lore for races up to this point, providing more role-playing opportunities for those inclined to seek a more melancholy cultural narrative.

This identity doesn’t fluctuate further – this is very important. Despite the changes throughout the editions, tiefling lore has remained constant throughout. For the sake of brevity, I won’t go through every edition, but it is worth mentioning that 3rd Edition is a bit of a gap for them; for much of this edition, they were only entries in the Monster Manual. They resurface as a player race in the Forgotten Realms Campaign Setting, where they get a new label of “outsider” but no significant change to their niche as exiles without a home. They have been a core player race for both 4th and 5th Edition, both times bearing the same role of being an outsider without a plane to truly call home, both times bearing their elemental resistances and spellcasting deriving from their heritage.

(As an aside, I find it heavily amusing that the Svirfneblin Deep Gnome entry is longer than the gnome entry is in this campaign setting – and yes, I am a bigger fan of the deep gnome than the original gnome itself for this reason).

The tiefling identity is further reinforced by the character Annah-of-the-Shadows in the video game, Planescape:Torment (1999). If you’ve never played the game, I highly recommend you go listen to the Companion Dialogue videos – it gives you a really eye-opening idea into how the developers conceptualized tieflings through the lens of this single character.

These screenshots from the game don’t really do her justice…but they do show that again, the “orphans of the planes” identity has a lot of staying power.

Tieflings are not yanked back and forth by dissociative decisions, and this is to their benefit: they remain consistent and iconic since their introduction, and a player who asks about their features can be given primarily associative justification for all of them: they have their unique appearance due to their connection with the Lower Planes, and the resistances and spells they bear echo those of the devils they derive those traits from.

So, what can we conclude from this quick jaunt through D&D’s past?

Taking five editions of a game and running through them within a single blog post means that we are neglecting many of the details crucial to the design process, but we can take away overarching lessons from it – that dissociative design can lead to sterile, flavorless, and ever-fluctuating ideas, while associative design can lead to an idea with real staying power. I stand behind the idea that when inventing a race for any game, that race should inspire new avenues of play rather than merely providing another race on a list. In the realm of tabletop roleplaying, those new avenues should include the stories and conflicts you can explore with that race.

If the race doesn’t do that, and still doesn’t have a stable identity even with the world’s most popular MMORPG providing some of the flavor, then it’s a flop. Cut it out of your game.

Despite the blurb and my well-known exasperation with gnomes, as a reader I hope your takeaway from this isn’t that gnomes suck. If you already held that belief, feel free to enjoy personal edification that my research further validates your view, but that’s not really the point. Gnomes as they exist in D&D don’t really present a problem for the popularity of the D&D game. The point is what to do for your own games.

- Don’t just copy races over from D&D without considering their origins – what makes those races work in D&D? Do those qualities still apply for your game? Should you rework the races? Should you make your own instead? These are important questions.

- Don’t fall into the trap of feeling like you need to meet a certain number of races simply to meet a quota, or to adjust the total number. This is a dissociative choice, and will not lead to an interesting race by itself.

- Don’t assign a race to a new location and expect that alone to carry the race’s identity. Especially don’t do this if it’s a patchwork addition to a race with an identity problem.

- Don’t provide class bonuses to a race as a way of making it stand out. There’s nothing wrong with linking class and race, but that should not be part of the arithmetic for why a race needs to exist in your world.

- Don’t assume that a race that works in a story will translate smoothly to the game you create – you will need to make changes to fit them into your game, and it’s important to consider whether the race remains worthwhile after those changes are made.

- Do create races which carve out new niches of play through their cultural place within your worlds. Think about how they relate to others and make sure these relations are clear to a player reading about your race for the first time. These associative links help not only to ground your race, but to provide roleplaying hooks for players to grab onto.

- Do pay attention to how consistent your race is over time. Even if you don’t have the luxury of a game with multiple editions, you still have your own design process. If a race’s fundamental identity changes multiple times during that design process, look into why. Are associative choices being made about the world (for example, tieflings are simply “outsiders” when a campaign setting wants to downplay the Planescape cosmology), or are you making dissociative choices (for example, gnomes are given the bard favored class because illusionist is wrapped up in wizard, which is already favored by elves)? Be cognizant of what drives those changes, and ask yourself if your race’s identity is too nebulous if it’s constantly changing.

Next time, we’ll look at some more races, using a different metric.

P.S. The dissociative realities around tieflings are also exciting, though they weren’t too pertinent to this post – effectively, tieflings were a countercultural response to the removal of demons and devils from D&D in the 80s due to backlash from Christianity. This article goes into some of the decisions made regarding tieflings, including why they are called “tieflings” – which is closer in meaning to “creature from the depths” rather than the expected “creature from hell”. Give it a read if race design fascinates you!

Works Cited

Featured Image by Jason Engle.

Avellone, Chris, and Colin McComb. “Planescape: Torment.” Planescape: Torment, Beamdog, 2017, http://www.planescape.com/.

Cook, David Zeb. A Player’s Guide to the Planes. TSR, 1994.

Cook, Monte, et al. Dungeons & Dragons: Player’s Handbook, 3.5 ed. Renton, WA: Wizards of the Coast, 2003.

Greenwood, Ed, et al. Forgotten Realms Campaign Setting. Wizards of the Coast, 2001.

Gygax, Gary. Advanced Dungeons and Dragons. 1st ed., TSR Games, 1978.

Gygax, Gary, and Dave Arneson. Dungeons & Dragons. 1st ed., Tactical Study Rules, 1974.

Gygax, Gary. “Q&A with Gary Gygax.” EN World RPG News & Reviews, EN World, 29 Aug. 2002, http://www.enworld.org/forum/showthread.php?22566-Q-amp-A-with-Gary-Gygax.

Matt. “Gnomes.” The Dragonlance Nexus, 15 Sept. 2005, http://www.dlnexus.com/lexicon/13444.aspx.

Nowadays Gnomes and Halflings are basically indistinguishable, with Gnomes just being a bit more magical versions. You could merge them (like I did for my own setting) with little loss. I imagine they’ve rooted into DnD enough at this point to continue into future versions, I’m curious if they’ll have an identity overhaul in the future.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yeah, the ability for D&D devs to “fix” any identity issues is hampered by the fact that their audience is now attached to a lot of legacy ideas. It’s why I frame this more around “what to think about when you design your own game” or “what to think about when you GM” rather than how to necessarily adjust existing games.

LikeLike

Never liked gnomes, but I think my dislike for tiefling comes from the kind of players that are attracted to playing them. I’ve had loner tieflings in my games screwing up the mood before – really dislike ~lonewolf~ type in a team-oriented RPG.

LikeLiked by 1 person

But I agree that they do have a sense of identity as a race. I just wish the planar thing was more focused by players instead of the loner feel. Instead of demons and the like, what kind of tiefling do you think would be nice to be used more often? Fey-tieflings? Divine tieflings (pls no mention of Aasimar they are boo)? GOO tieflings?

LikeLiked by 1 person

So, if you create a game with planes as part of the core rules (so your game is world-linked to planar cosmology) I think you could do things to help the planes stand out by talking about a very different psychology or even a body plan.

There’s a lot to think about when doing planes, right. Do you want something super relatable to mankind in your game, in which case you end up with Genasi and Tieflings and basically just make a fantasy heartbreaker themed for Planescape?

Or do you want to emphasize the alien nature of other planes, in which cases your race design is going to take after maybe Eclipse Phase or the monsters found in Lamentations modules?

Those are the sorts of questions you ask when you make planar stories central to your game…shy away from rebuilding tieflings over and over.

As for loner players, I think it’s valuable to just tell players that roleplaying these more exotic races is tricky. Give them some roleplaying tips to help them out, and ask the other players for input too, if that *particular* character and getting it right is something you’re all invested in.

If you’re not invested in that sort of play, just tell them to tone it down. Worst comes to worst, you could always just tell them their playstyle is incompatible with your GM style.

LikeLike

neat

LikeLiked by 1 person