Jeff Rients has peppered the OSR discourse with his wisdom since 2004, and one of his most-cited posts is twenty quick questions for your campaign setting. Scrap Princess made her own list, filled with the frenetic queen energy that she always brings to any project.

Here’s my problem: neither of those lists do much for me.

They’re terrific, no doubt about that, but…well. At some point you gotta make your own. I heavily queried the RPG Talk discord, Chris McDowall’s OSR discord, as well as my own players in making these questions. Thanks to you all for your help!

If you want yourself a campaign setting for Dungeons & Dragons, this is my best foot forward in getting you started:

There is a lot of verbiage ahead. if you just want the 20 questions with no extra noise go HERE (click).

TWENTY QUESTIONS FOR YOUR D&D CAMPAIGN SETTING, ANTHILL-STYLE

show both questions and answers to your players. they are meant to be shared.

1. What is something that players can interact with that inspires wonder in your setting?

Each question will be annotated with some additional considerations. For this first one, I’m basically saying, “prove that your setting is exciting!”

With the crucial subtext of “is this something real, a ten-armed warrior your players can meet, a flying library your players can take books from, or is this an indulgent worldbuilding bit that would never see the light of day in play?”

Remember, if it didn’t happen at the table during gameplay, it’s headcanon. This applies to character backstories but also to world/plot points the GM hasn’t introduced yet. Neither as a player nor as a GM should you fall into the trap of evaluating your campaign based on headcanon rather than actual content.

2. How does one religion in the world work? What rituals and observances are involved, and how does this religion play with other religions out there? Are gods real?

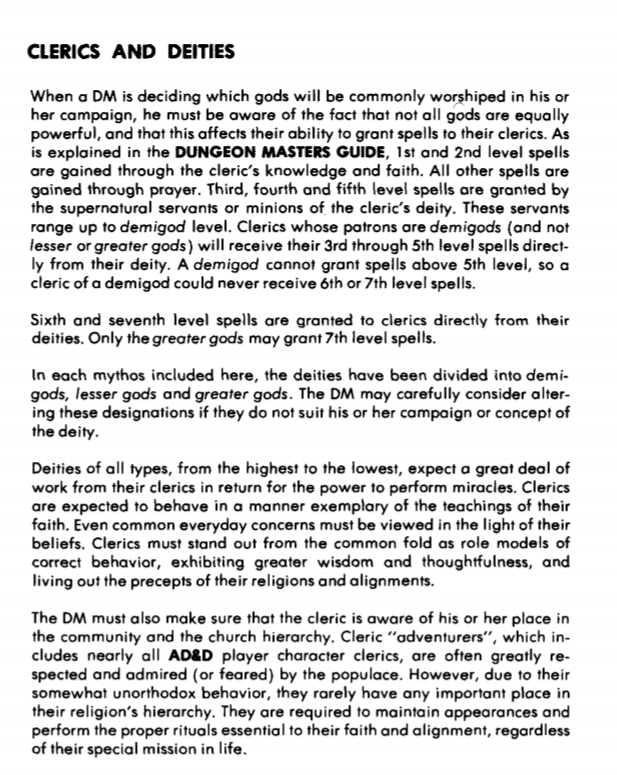

How deeply do you think about religions, and do religions bring harmony or conflict to the game world? The example you answer #2 with may not be “indicative” of what players actually experience in your next campaign or one-shot, but it still is instructive – players will get a glimpse of how you think about such things. It’s worth noting that Mentzer says the following in his Basic D&D Red Box:

“In D&D games, as in real life, people have…theological beliefs. This game does not deal with those beliefs. All characters are assumed to have them, and they do not affect the game. They can be assumed, just as eating, resting, and other activities are assumed, and should not become part of the game.”

Yet at the same time as this came out in 1983, you had products like Supplement VII, which provided examples of gods and myths to use in D&D, and Deities & Demigods, which says the following:

Suffice to say there is a lot of room for a Game Master to take religion, be it tossing the whole concept in the bin or building up elaborate sociopolitical messages within their religious canon. Act as according to your interests, and those of your players.

3. How does one get access to goods and services in the setting? Will items always be available, will trade routes be jammed up by bandits, are there commissions for things, are magic items sold in regular stores, are hirelings available for hire or do we have to find them in the world?

We all understand that since D&D is a game, there will be allowances made for abstractions in the market. The degree to which those abstractions exist may vary. In one game you might be able to “buy everything in the core rulebook we are using”. In another game the GM may “have a list of things in stock”. In one game, hirelings may be a matter of finding cool NPCs with charming personalities that you ask to join you because you’re cool, they’re cool, we should all be friends. In another game, hirelings may be faceless mooks you hire by going to the tavern and putting up job postings.

4. What are some examples of people and creatures a commoner would be wary of in-setting? What are some examples of people and creatures a commoner could trounce without worry? What are some examples of people and creatures a commoner would trust?

Inherent in this question is a curiosity about both stakes and culture. In some games, a strict reading of the mechanics suggests that a cat could easily kill a level 1 PC. So even getting into a fight with an alley cat is a stupid idea. Understanding this on a diegetic level can be helpful. If a noble comes up to you, in this world are they to be trusted? What if a vampire comes up to you and says they are a citizen? What about an orc, or a goblin?

5. Name a heroically slain dragon, or something comparable in threat. How was the creature slain, according to stories? How was it actually done? Was it a fluke or a well-executed slaying of a monster?

This is about how heroism is meted out. If in your world, the last major slaying of a creature was done through a one-on-one fight, that conveys to players that one-on-one fights are something they will be able to do. If in your world, the last major slaying of a creature was done by tricking it into a rockslide, players will approach such threats very differently.

6. How do people who adventure (if there are even such people) get jobs and contracts in this setting?

Adventuring guilds? Noble contracts? Freelancing? Just good Samaritans willing to help anybody in need? Plundering a dungeon for gold and glory?

7. How do people convey their station/caste if such things exist? In particular, what intersections do station/caste have with the adventuring lifestyle (whatever the players are in the setting…guards, tomb raiders, bounty hunters, etc.)?

Does citizenship matter? Can players, by virtue of their backgrounds, get access to unexpected privileges? Conversely, would players, by virtue of their backgrounds, be punished or distrusted by default?

8. What privileges and prejudices exist in your world, if any do at all? For example: How does the world view LGBTQ identities, ethnic identities within each fantasy “race”, and race relations?

Primarily this question is one that touches on player comfort and GM comfort with these themes. How you answer this question may change depending on your players, and this question may focus more on one or two of these categories rather than all of them, again depending on your players.

Examples of a concrete formulations of this question are:

“how are homosexual relationships treated?”

“how are orcs treated?”

“what communication difficulties are there between beetle-people and dwarves?”

Start with something like these if the entirety of #8 is too broad to you. Specifically regarding the orc question, bear in mind that whenever monstrous humanoids are monsters and not people in your setting, that can result in the indulgence of racist fantasies. Think about whether you this might happen in your group or not, and what protocols you will use if discomfort emerges as a result of your worldbuilding.

9. What is the distal view of the political system? Is it feudal, is there a suzerainty, do we have a triumvirate, etc.

10. What is a more proximal view of the political system? Who are local nobles or leaders that should be known about, and what are their reputations?

#9 and #10 introduce power structures that not every campaign will have. They do serve different purposes though. If you were playing in the Game of Thrones setting, #9 would be a mix of monarchy, the importance of bloodlines and birthright, and how dragons can turn everything upside-down in a case of might-makes-right. #10 would be stuff like “Eddard Stark is a man of honor” and “in the North, leaders are expected to carry out executions by their own hand”.

11. Do your players even need their rations and torches?

Whether or not this has to do with worldbuilding is up to you. In Patrick Stuart’s Veins of the Earth campaign setting, light isn’t just a resource, it’s part of the genre, there’s a space on your character sheet for your lamp, and nearly all the denizens of the dark have their own unique cultural and biological responses to light.

For most games though, this question is where you give your players an idea of how seriously they need to take starvation or dying of thirst. And by extension, how rigorously they need to understand your foraging and hunting rules.

12. How do you become a ruler of many?

Answering this question teaches your players what is necessary to build trust. If your answer is “you just have to be born into it”, that’s going to create a very different vibe from if your answer is “you should listen to the issues of those you rule and provide tangible solutions” or “gold and glory earn you trust”.

It’s sort of easy to throw this question away I think, just by using real-world answers and common sense. But I think you could answer this in ways that really amplify your setting too. For instance, in Twig, those in positions of power usually undergo extreme surgeries to become literally superhuman. Augmented skeletons, senses, and severe etiquette training reinforce the notion of what a noble is and why they have the right to rule…which adds significant texture to a campaign setting.

Part of this answer also means explaining how to socially climb. Who do you talk to? Do you need to earn the favor of the 13 Icons of the Dragon Empire or do you need to find the Lady of the Lake, who will grant you divine right to be king?

13. Are there social consequences for necromancy or other forms of forbidden magic? Do these consequences differ in the view of the common man vs. other people?

14. What is the common man’s capability to distinguish the following things: a werewolf’s tracks vs. wolf tracks, a manticore attack vs. a lion attack, a demon attack vs. a gargoyle attack?

Both of these questions are about how players interact with the setting. How reliable are accounts they hear? How much can they reveal about themselves?

15. What is the social position of rogues, within both history and in the current day? Within both thieves’ guilds and within the world at large? If you run the game using specialists or antiquarians or courtesans or some other such thing, treat this question as if for those. If you run with no analog to the rogue, or if you run a classless game like Knave, you can re-flavor this question for any influential social organization of your choice. “What is the social position of the Blue Monkey Tamers of the Invisible Moon?”

Are there tithes that thieves’ guilds take? Is there a large criminal syndicate in the setting or a bunch of decentralized pickpockets? Are thieves meant to be charming scoundrels that bring life and character to the world or are they distrusted by virtually everyone? What is the biggest achievement of the criminal underworld, and what is their most wretched disaster?

16. What is the role of dungeons within the world – are they a place where MacGuffins have been hidden, ruins of lost civilizations, unexplored caverns, Zelda-like puzzle dungeons, or something else entirely?

17. How common are dungeons, how deep or large are they, and how much treasure might be expected within their depths?

This pair of questions might cost you some of your setting’s “mystique” to answer. All the same, whatever answer you give can help players understand your setting better. D&D does not require dungeons, but does tend to focus on them, so knowing what a dungeon is, formally, is useful. This is also a place to set expectations – if your players expect hoards of gold within every abandoned keep they find and all you offer them is a lot of squatters and some ruined furniture, that can be a hard reconciliation to make between expectation and reality.

18. Explain the differences between magic-users in the world. For instance, how would wizards, sorcerers, miracle-workers, warlocks, witches, medicine-men, stage magicians, and the like differ from each other? Do such categories even exist?

19. What are two examples of food culture in the world? Even if food isn’t a part of play, what dishes are people consuming in the world around the players, and what messages can be conveyed through food and drink?

For example, can you warn a tribe of invasion by serving them their clan animal? Could you poison a wine that you know only the princess drinks, and no one else enjoys? Could you give the secret recipe for a dish from one tavern to another for some amusing drama, or would people actually get hurt in the fallout?

20. What is the internal logic of the game world you are running, as far as players are concerned? When the players act and the world reacts, what principles do you hold to?

The most widespread responses to internal logic tend to be “be a fan of the players”, something started with the Powered by the Apocalypse games…which usually means that your world will react in dramatic ways that keep the story moving…

…and “the impartial referee”, something that’s oft-repeated in OSR circles, and which appears in Matt Finch’s A Quick Primer for Old School Gaming in the following quote:

“A good GM is impartial: he doesn’t favor the party, and he doesn’t favor the monsters. But he’s not playing a tournament against the players, where he’s restricted by rules and required to offer up well-gauged, well-balanced challenges. Instead, he’s there to be an impartial referee for the characters’ adventures in a fantasy world – NOT in a ‘game setting’.”

People interpret this in different ways, but to me it means that the world will react in ways that stem from “what reality demands”, rather than “what drama demands” or “what good game pacing demands”.

However you understand the above, I think there are far more answers than just those two, and I think that understanding the internal logic of the world, a.k.a. how the GM decides what happens next, is helpful for players of all backgrounds, both new and old. My own examples of answers to this question are varied enough that I’m giving them their own section below.

INTERNAL LOGIC FOR YOUR D&D CAMPAIGN SETTING

or: anthony’s way-too-long-answers for question #20.

Railroad

As a GM, I tell stories which players participate in. There will be many moments where you must overcome individual challenges with tactics, player knowledge, or with character abilities, but the overall path of the campaign is more or less pre-scripted. The more you participate within the story, the more of the story you will see, until we eventually reach a conclusion together. Going “off the rails” means there isn’t as much to do or see, and the world will endeavor either actively or passively to see you back “onto the rails”.

Multiple Rails/ Find the Railroad You Want

As the GM, I prepare multiple stories and players can choose which one they wish to participate in. The more you participate within the story, the more of the story you will see, until we eventually reach a conclusion together. Going “off the rails” completely can mean there isn’t much to do or see, though you could go onto another railroad.

Main Quest & Side Quests

As a GM, I will seed hooks for a quest that players to embark on, though I don’t necessarily prepare or know it will end. There are many side quests that might also come up, if players get bored of the main quest. Ultimately, I center the world on the player’s journey – that is the scope of the game. Players can do other things outside of quests and side quests, but it will often serve as a diversion and not be particularly meaningful in the big picture. How the players choose to fulfill the quest is up to them, and we will discover that ending together.

Side Note: the vast majority of TSR/Wizards of the Coast modules are either Railroads or Main Quest & Side Quests. Even dungeons are arguably structured this way, with some reason you’re in the dungeon as the main quest and everything else seen as a side excursion or obstacle to that main quest.

Many iconic campaign settings were historically conveyed to players through adventure paths and modules that followed this model – Planescape, Ravenloft, Mystara. As a result, a lot of GMs see this as the default internal logic of fantasy worlds. That can work! Just be aware it doesn’t have to be how your run things.

Multiple Quests/Find the Quest You Want

As the GM, I will seed multiple hooks for multiple quests that players can embark on. None of them have pre-ordained paths or endings, and players may fulfill many or none of these quests. Ultimately, I center the world on the player’s journey – that is the scope of the game. Players can do other things outside of quests, but it will often serve as a diversion and not be particularly meaningful in the big picture. How the players choose to structure their journey is up to them – they have the building blocks in the form of prepared quests, but the ultimate thing they build is something we will discover together.

Player-Independent Plot Lines

As the GM, I prepare a lot of plots and events involving NPCs which will progress with or without player involvement. If players show interest in a plot, either intervening, trying to act upon it, or tying their own goals to those existing events, my job is to have the process be well-paced or suitably dramatic. However, despite trying to keep a dramatic and narrative thru-line for these events, the world isn’t centered on the players anymore. They are just inhabitants of the world that the game is focused on – the world moves on around them, and there is no longer this sense of “player-facing quests” that they are “meant” to go on. Whenever players interact with the world, I will try to have the world react with what pacing demands – plot twists, heartwarming moments, betrayals, etc., to keep the campaign engaging.

Narrative Sandbox

The world is an open, fantastic space for players to explore. Various situations will develop in the world, and players can choose to be involved with these situations or not. My job as the GM is to prep situations, not plots – I prepare a set of circumstances. The events that follow from those circumstances may depend on actions the players take, but can also happen without their involvement at all. The world goes on without the players, after all. Ultimately players are responsible for generating their own goals, while my job starts to approach impartiality: I am providing them a space where exploring those goals is possible. Whenever players interact with the world, I will try to have the world react with what pacing demands – plot twists, heartwarming moments, betrayals, etc., to keep the campaign engaging.

Side Note: To me, what distinguishes a sandbox from other forms of internal logic is that, for most of the other forms of internal logic, the GM would reasonably assume that “the real job of the GM, and by extension the world, is to make sure people have fun”.

The sandbox GM and by extension the sandbox world disagrees with this assertion. It is not the job of the GM to make sure that people have fun (I am paraphrasing from Macris’s book, Arbiter of Worlds). Rather, the GM’s responsibility is to create an environment where fun is possible, and then to run it as stoically as possible.

“Imagine that you are hosting a party: your job is to provide the right mix of appetizers, drinks, ambiance, and crowd so that people can have fun. It’s not to act like a clown because Rob had a bad day at work. This is a subtle point, but if you keep it in mind, you’ll avoid a lot of self-inflicted doubt and stress about your role.

…I believe the great enjoyment elicited [by sandboxes] is a result of creating a sense of agency among their players. In an RPG, by making choice X, the player can impose result Y, which is the essence of agency…the players must be able to make real (not faux) choices that have meaningful consequences on the players and their world. And that’s a requirement which is in direct opposition to storytelling, or to [taking sole responsibility for fun and trying to] making sure everyone has fun.”

Realistic/Procedural Sandbox

The world is an open, fantastic space for players to explore. Various situations will develop in the world, and players can choose to be involved with these situations or not. My job as the GM is to prep situations, not plots – I prepare a set of circumstances. The events that follow from those circumstances may depend on actions the players take, but can also happen without their involvement at all. The world goes on without the players, after all. Ultimately players are responsible for generating their own goals. When they interact with the world, I will try to have the world react with what realism demands – this can mean following a set of comprehensible rules to determine what happens, such as following wandering monster tables, restocking tables, getting lost in the wilderness rolls, or reaction rolls strictly. It can also mean following logic as best as I am able – running things in a consistent, fair, and impartial way as possible.

What is perhaps most important for the most stringent sandbox games is for players to have a framework of cause and effect that honors their agency above their “fun”. If they always meet something dramatic, or satisfying, or if I’m focused on making them believe their choices are always the right ones, this is just sleight-of-hand. It is still an art, the same art that a skilled novelist can use to make us believe that a favorite character is in danger, even though he’s not. But even though dramatically appropriate and fun outcomes that defy probability lead to a wild ride, it is still the GM dictating pace, rather than letting players choose.

The strict code of sandbox GMing yields a different set of priorities for their world: in order to make sure that agency is maintained, the world will let players make choices that lead to results that aren’t fun. You as the GM can’t guarantee the fun, and your world will not bend to accommodate players if they make a choice that leads to boring or unfulfilling results. This in turn makes their successes feel all the more earned – it was achieved through their own actions, not through your sleight-of-hand. Thus, you best honor their agency.

One thought on “Twenty Setting Questions, Reredux”